In this episode of Against the Sales Odds, Lance sits down with Loren Feldman, the Founder and Editor-In-Chief of 21 Hats. Loren brings us through his journey as an editor in a newspaper, magazine, and more, from his time at Inc. to his founding of 21 Hats. He enlightens us on how to have the right mindset and how to understand your audience honestly. We can see Loren’s unique ideas on how to approach challenges, ask questions, and listen to and understand feedback from others. As Lance and Loren move through the episode, we see the different engagement philosophies of being proactive in business! Learn more about Loren and 21 Hats by subscribing to his newsletter at http://21hats.substack.com.

—

Listen to the podcast here

Transforming Your Perspective: A Fresh Approach To Understanding Your Audience With Loren Feldman, Founder And Editor-In-Chief Of 21 Hats

I’m so excited about this episode. I have Loren Feldman on, the Founder of 21 Hats. He’s going to tell you what 21 Hats means in a second. What it’s about my experience with Loren is he gave me an opportunity when I wrote my first book. He was on the Wharton network on SiriusXM radio and he gave me a couple of shots to get on the radio with him and talk about some things about business, which I was so grateful for. He then started his platform, 21 Hats. Welcome, Loren, to the show. I appreciate it.

I am so happy to be here, Lance. Thanks for having me.

We’re two Philly guys around Philly so we have that in common. Tell the audience what 21 Hats is.

It’s a community for business owners. The 21 Hats, not everybody gets right away, refers to the fact that to build a business, you’ve got to wear a lot of hats. We’re here to try to help with that.

There’s no doubt, I can tell you. During the pre-game of this conversation with Loren and me talking about wearing 21 Hats, he and I were at a whole deep end that I brought up to him because I know he has such a wealth of knowledge on it with his guests and his community. I was talking about succession planning and protecting the organization.

I was getting asked by a board member questions I couldn’t ask. I had to go back and ask other people. We were talking about retaining employees and protecting the organization and what it looks long term. Loren is always dealing with business issues and the different hats that people wear. When I first met you, you would have me deal with the sales and marketing hat. That was the hat I was wearing with you.

On that radio show, we used to take questions from callers. You were good at your feet.

I remember talking to one of your callers and the guy was like, “I’m on the Pennsylvania Turnpike right near Fort Washington.” I’m like, “I know exactly where you are.” He was a live caller. You’re running an organization. You run this community and you have a powerful podcast. Tell everybody what your podcast is real quick so they want to dive deeper into this.

Our main offerings are the daily email newsletter, which is for business owners in which we highlight the most important news of the day, specifically for business owners. Not everything is out there. Just all in one place. Some of it is from obvious sources like the Wall Street Journal. Much of it is from obscure places that we find, things that we think are useful for business owners. The podcast is primarily a weekly round table peer group discussion. I have 10 regulars and I talk to 3 of them each week.

Unlike a lot of business podcasts, it’s not about people who’ve had huge success, who are remembering their careers and talking about a few of the bumps on the road. These are people who are fighting the good fight in the trenches every week, figuring out how to do this and that, and kicking around ideas. It’s a lively conversation. Sometimes people are happy because things are going well. Sometimes we have tough conversations because things aren’t going well at all. I do have one-on-one experts from time to time, such as you, Mr. Tyson.

Me truly, yes. I always appreciate you asking tough questions. Like anybody on here, the whole audience, we have business leaders, entrepreneurs, and salespeople who are budding entrepreneurs but if anybody knows anything about my philosophy, you’re constantly running your business. It’s the business of one. A lot of your advice is timely and the way you frame things, I love it. Loren, I like to ask everybody this. Where did you start? How did you get 21 Hats? Bring us through a little bit about your journey and story.

I’ve always been a journalist. I went to a good business school called Wharton, where I spent way too much time working at the school newspaper and didn’t learn as much business as I probably should have. I was a sports editor of the school newspaper and I loved that. I started as a sports writer. I did that for maybe 4 or 5 years and realized that there were a lot of other people who wanted to be sports writers but there weren’t as many people who wanted to be business writers.

Understanding Your Audience: There are a lot of other people who wanted to be sports writers, but there weren’t as many people who wanted to be business writers. There was a lot less competition, and it looked like the opportunity to move up quicker would be much greater covering business.

There was a lot less competition and the opportunity to move up quicker would be much greater covering business. I switched and was glad I did. I love sports but I found that covering business was very similar in a lot of ways. There’s a scoreboard in business too. It’s not always as public or obvious but it exists for everybody. Ultimately, they’re people’s stories as they are in sports. That’s what I liked about covering sports.

When you were at Wharton, you were writing sports but you went to Wharton School. Your first role coming out, was it a sports role or a business role?

It was a sports role with a newspaper that no longer exists, The Patterson News.

You’re up in Jersey. Is that a Jersey newspaper?

Yes. I then spent about three years working for a newspaper you’ve heard of called The Columbus Dispatch.

I did not know you were at The Columbus Dispatch. Every time I talk to you, I learn something new about you. I’m curious and I always meant to know this story inside. You’re a sports writer at The Patterson paper. Do you have to pitch your story to get your stories in? Are you assigned stories? Is it both? I’ve watched enough TV to think I understand the process but I was always curious about how it worked.

Like anything in most industries, you start at the bottom rung. When I started in Patterson, I started on the sports copy desk. I was reading the stories and editing them for the other sports writers there. Over time, I pitched ideas. Occasionally, they were accepted and the story was assigned. Eventually, I got a beat. I didn’t stay there that long in part because there was a very difficult labor battle that broke out there. When Bricks started going through windshields, I decided to look for something else. Luckily, I had a couple of contacts that put me in touch with the sports editor of The Columbus Dispatch. That’s how I wound up in Columbus.

You lived down here for four years?

About three years in the ‘80s.

Where did you live? What area? Were you downtown?

German Village.

It’s good food down there.

It was a lucky time to get there. I had a great experience in Columbus for a couple of reasons. One of which was I was a very young staff. I got there in my early twenties. While I was there, there were a bunch of people who had their 25th or 30th birthday working at the paper. I fell in with a good group of people. Some of them are still there. Some of them I’ve kept in touch with. It was a great group and experience for me.

With the transition, were you still in sports when you got to the dispatcher?

I was but it was in Columbus where I switched to covering business. I had a great time there. A lot of people don’t know this but, in many ways, Columbus is the fast-food capital of America.

They have no clue, do they? They don’t even know. Nobody even knew that White Castle was from here.

I did. I wrote about it in the ‘80s. Wendy’s started there. It was a little bit like the dot-com bubble, believe it or not. Wendy’s came out of Columbus and made a whole bunch of people, including the governor of Ohio, millionaires pretty quickly. When that happened, it made it possible for almost anybody to raise money to open a fast-food chain. Everybody started throwing ideas and I started covering the craziest ideas you ever heard.

My favorite was there was a fast-food chain called Prosciutto and Chins. The idea was to sell both Italian food and Chinese food that would be cooked in a central kitchen and distributed through Fotomat kiosks around the city. That was the idea. They wanted to replicate it around the country. Somehow, it didn’t work out for some reason.

It was ahead of its time. You get a lot of these fusion restaurants like Chipotle. What’s interesting about Columbus too is it’s a retail capital. You got Abercrombie & Fitch and all of the Les Wexner brands and retail pieces of stories inside Victoria’s Secret to limit it.

The other thing was that it was a test market. That’s in part because it’s not surrounded by a lot. Especially when I was there, it was surrounded mostly by cornfields. That meant that P&G in Cincinnati could come up, test a product, advertise it in Columbus, and not worry about those ads bleeding over into other markets. It was clean. That was part of what worked for fast food because the belief was that if it worked in Columbus, it’d work anywhere.

It’s a crossroads. It’s within 500 miles of 50% of the population in the US so people have migrated to this state. That’s why I’ve stayed. I didn’t know we had two areas of the country in common, Philly and Columbus.

It’s remarkable.

We’ve talked five times and I didn’t even realize that. I’m curious back to something else. When you’re pitching those ads or stories, do you pitch the headline first or the concept first? It’s writing books. I’m talking to publishers and I’m always wondering what’s the move. Where do you go with the attention-getter?

Usually, the concept. It helps. It’s a joke in the business. A lot of people come up with a headline first. If you come up with a great headline, you’re going to find a story to run under it because great headlines are priceless. We don’t want them to go to waste like with book titles.

Great headlines are priceless. You don’t want them to go to waste, just like with book titles.

That’s why I ask because sometimes as entrepreneurs, they’re very product-heavy and sales-poor. They don’t connect the branding to it. My first book, Selling Is an Away Game, took off right away because it has a great title. We went through iterations of the human sales factor. As we built the book, because the title was off, to begin with, it became a little bit of Frankenstein.

When I say Frankenstein, it’s my favorite book that I wrote because it’s so wide but because the title was off, it was hard. I linked that to so many things in business. I linked it to the concept of product, go-to-market, and how to sell things. I look at menus when I go out to eat and I’m like, “Only The Cheesecake Factory or BCakes can pick off these monster menus that are hard to sell.”

A good headline is a good elevator pitch. Until you have those things, you don’t know what you’re doing. I talk to business owners all the time. I often help them with their communication and talk about how they’re trying to describe what they do. It’s surprising to me how many business owners are not as good as they should be at stating quickly and efficiently what exactly their business does. It’s so important. You have to be able to do that, both to sell the idea but also to think about what your business should be doing, what falls within the walls, and what falls outside.

If you think about the cousins to that, I did a seminar and somebody had asked me, “What’s one of the key skills to hiring salespeople at this point?” I said, “One of the key skills is very fundamental problem-solving and critical problem-solving skills. Being able to state the problem is the key to both.” Even if you’re dealing with stress and worry, fundamental problem-solving comes in. What is the problem? What is the opportunity? What are the causes of it? What are the possible solutions? What’s the best possible solution?

You get very Stephen Covey with things. Stephen Covey says, “With anything, begin with the end in mind.” I think of that headline or concept as a business owner or salesperson. Thinking further, people struggle with where they’re going with their careers. It’s because they chase money. Money follows but never leads because fundamentally, they haven’t begun with the end in mind. There are so many cousins to that so wide. That’s why I was curious from your end. To get where you are with this community that you built and these people who keep coming back to you for advice, I don’t think you get to 21 Hats without knowing the analogy that it takes 21 hats as a business owner. I love that.

I knew something about business. I was in business journalism for a while. Many years ago, I wound up at Inc. Magazine where I first discovered entrepreneurial journalism. I thought I knew something about business but I knew nothing about entrepreneurship. I had my eyes open there. I fell in love with it. My strategy was I find the smartest person and the best writer there. I stayed by his side and learned everything that he was willing to teach me. I got introduced to all kinds of great people through him. I fell in love with it. Without that experience, I never would’ve had the understanding to come up with 21 Hats.

In a nutshell, what is the difference between business journalism and entrepreneurial journalism?

Business people and journalists come from different directions. Business journalism can be a little bit of a leap to understand for many journalists. What it’s like to be a business owner is an even bigger leap, especially for journalists. I’ll give you an example. Look at something like a business that has to go through layoffs. Most journalists will react to that instinctively with a reaction along the lines of, “That’s terrible for the employees,” which it is but without any understanding of how terrible it can be for the business owner as well.

Understanding Your Audience: Business journalism can be a little bit of a leap to understand for many journalists, but what it’s like to be a business owner is an even bigger leap, especially for journalists.

Laying people off may be harder for the employees who lose their jobs but it’s no picnic for the business owner who has to go through that and has to face up to the realization that something hasn’t worked right and something probably has to change. It’s about that. Being a business owner is an entirely different experience and civilians of all stripes, including journalists, don’t naturally understand and realize all that it takes.

Here’s another example. I worked with some of the smartest business journalists in the world at Forbes, The New York Times, and Inc. Very few of them had any idea that it’s routine for a business owner to put their home up as collateral for a bank loan. For many journalists, the idea that you would risk your home to try to build a business sounds like crazy talk. They think people on Wall Street and Silicon Valley are taking risks. They are but they’re taking risks with other people’s money. They’re not taking risks with their home. It’s understanding things like that that is essential to understanding entrepreneurship.

That is so well stated. I was in a conversation with one of our board members. Usually in a two-year stint, I pick whatever skill that the business is going to need and we add a board member that would bring that level of expertise. One of my board members owned at one time a very large Professional Employer Organization or PEO, where essentially, they did a lot of consulting but they’re taking on the risk of having employees. From an HR standpoint, they can protect the company, which may not be solvent or successful enough. I’m probably going to explain it as well as I do.

He was asking me about disability insurance. My controller was looking at it more as an expense. He said, “The worst place to be on is if you had somebody that you had a struggling business, something happens to somebody, and you need the role but you can’t afford if somebody’s not working in the role because they bring a return on investment.” I said, “The theory of souls.” He goes, “What do you mean?” I said, “Typically, if you’re ever at the front of an aircraft and you listen to a lot of captains, they’ll say, ‘We have 231 souls on board’, not passengers. What you’re saying is there’s a different EQ or empathy that’s tied to an entrepreneur because, godfather one, it’s all personal.”

Not that other businesses aren’t. Everything comes with a different zero. I read a book by a guy who was called Boyd. It was the guy who invented modern warfare and dog fighting. He says, “Everything in life comes down to either conquest or survival.” If you go to the very basis of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, it’s always survival first. We’re all trying to survive at some level. There’s also conflict inside that survival.

That’s why I fell in love with doing this. Those stories I thought were moving. Once you understand what the owners are risking, what they’re trying to do, and the ideas that they come up with, it’s a whole different world. It’s something that most of my colleagues did not understand. They understood that small business is important in the aggregate. It’s half the economy or close to it but why would you care about any one small business? It’s exactly for the reasons you articulated. Everyone is a story, a journey, and somebody’s passion. That’s what I love doing.

The other tricky thing about it though is that they’re hard to cover, the privately-owned businesses. Think about it. If you’re covering a public company, any idiot can go to Yahoo Finance and find out anything they want to know about what’s working or not working at that business. With a privately owned business, you’re not going to get all the numbers that you would like to have. Some owners are more generous about sharing that than others but they’re not going to give you everything. In many cases, an owner may not fully understand why the business is succeeding or failing. If they always knew, there’d be a lot fewer failures than there are.

If you look at them, 90% of most businesses fail after the first year to make it. I heard a statistic that only 4% of companies get above that 1 million to 2 million. There’s not a big percentage who get over that million-dollar mark. You’re right. You’re speaking of Inc. We were very proud of this. We made the Inc. 5,000 in 2023 but the questionnaire for Inc. 5,000 was invasive. Not in a bad way. I’m excited and I hope we go in 2024 but you could tell that Inc. understood small businesses based on the questions that were asked. You’ve got to certify your results because anybody can claim anything. You’ve got to share some things you’re not necessarily comfortable out there in the ether with. You were at Inc. for how long?

About 4 or 5 years.

From there, you went where?

I was there until two weeks after Lehman Brothers fell in 2008 when I was laid off along with the entire digital division. It seems like a weird time to lay off the digital division. The media business was being turned upside down. Every legacy publication had a difficult transition adjusting to the internet. Inc. was no exception. I saw that as the future. Around 2007, I seized an opportunity to switch from being the number 2 editor on the print publication to being the number 1 editor on the website, which I thought was going to be a good career move until I was laid off.

I wasn’t happy about that but it made sense. I wasn’t responsible for this, fortunately. We had some technological difficulties. We were trying to reinvent the website. We are trying to turn it into more of a community like what I’m doing. Back then, the software was much more rudimentary. Now, you can do everything yourself. Back then, we were hiring these expensive developers to try and build something from scratch, and it didn’t work. The project was years late, millions of dollars over budget. The owner of the publication eventually said, “I want to start from scratch.”

Doesn’t the owner of the publication own Inc.?

I’m not sure what you’re thinking. The owner of Inc. is the Founder of Morningstar Investments.

He owns the Chicago Fire.

I did not know that. He’s based in Chicago, I’m sure you’re right.

I heard a podcast with him on it.

Joe Mansueto.

You talk about a guy that has some common sense.

He’s done very well.

He does, especially how he grew Morningstar. Thank you for that. I couldn’t remember his name.

I was going through a tough time. I got laid off. It so happens that about 2 or 3 months before I was laid off, I was approached by the New York Times, which offered me the chance to come and start their version of Inc. Magazine as a web vertical. My answer was, “Thank you. I’m flattered.” I learned everything I know about entrepreneurship at Inc. I just don’t feel right about going somewhere else and creating a competitor for the people who taught me what I know. I got laid off and called back the Times. I said, “I’ve been thinking about this. If that job’s available, I’d be willing to take it.” Fortunately, for me, it was available 3 months later. I took it and spent about the next five years or so at the New York Times.

From what you can remember, what was the biggest culture shift between Inc. and the New York Times, in your opinion?

The Times was much further along in terms of figuring out the internet. At Inc., they were still in the stage that most legacy publications went through where they were thinking of the internet as a dumping ground. Their main product was the print product. They would publish it in print and a month or so later, dump it on the internet. They were not taking advantage of any of the tools or advantages that the internet and the web offer you, whereas The Times was slow on certain things but was way ahead of the game on this.

The Time was slow in certain things, but they were way ahead of the game in terms of figuring out the internet.

They saw where it was going. They had a vision for that.

By the time I got there, they had already concluded that breaking a big story on the internet is as good as breaking a big story in print. A lot of publications are still holding their best stuff for print. The Times wasn’t doing that. They were publishing the same thing online as they were in print but also looking for ways to take advantage of the tools that the internet offers you. One of the things I did was to start a small business blog where I hired a bunch of contributors, business owners, experts in particular areas, and journalists who covered aspects of business ownership and entrepreneurship. We published 2 or 3 posts a day and built a community around that blog.

You asked me about the culture shift. The biggest shift was although I had been editor of the website at Inc., we were still doing that dump thing. I wasn’t figuring out how to use the internet yet. We did do that at The Times and one of the things I figured out is that I had to up my game. I realized that because I published a blog post that had a mathematical error in it. We added up a couple of numbers incorrectly. A commenter corrected us on that within 30 seconds of publishing it. That’s a huge change. At a monthly magazine, if you get 3 letters 2 months after you publish something, you think, “I hit a chord with this.” With a blog, especially at the New York Times, we’ve sometimes got thousands of comments on a good interesting blog post.

It sounds like you started to realize from a community thing that this is a live conversation going on.

That’s exactly right. Part B of that is I realized that the response of the community was as important as what I published as a journalist. I had smart business owners and people writing for that blog post but the best post always elicited some conversation. Sometimes we’d get feedback saying, “Technically, that’s right but here’s a better way.” We always learned as much from the comments from the community as we did from the initial post. That was a huge difference.

If you took the first two roles at Dispatch and Inc. and then all of a sudden, you go to building this community New York Times. How did you change your leadership style, communication style, and perspective? What was the main thing you had to make an adjustment on?

The main thing was thinking differently about the audience. Traditional journalism had been very much a one-way street. We lecture. You listen and absorb. Some of it was ridiculous.

Part of the reason why media companies had such a difficult time with the transition to the internet is that they had this idea, especially in newspapers, that readers had a responsibility to read the publication. You as a citizen have to read the New York Times or The Philadelphia Inquirer. How else are you going to be an informed citizen? That’s your duty. That’s a terrible way to think about a business. It went about as well as you would expect it to go.

I switched from newspapers to magazines. Magazines had more competition and were a little bit ahead of the game. They were more aware. We’re competing for people’s time. Inc. may not have another business publication exactly like it to compete with but we’re competing with TV, movies, newspapers, and all the other ways that people can spend their time. We have to engage people but then it went a whole another level with the internet because suddenly, your audience can talk back to you right away. If you do something stupid, they’re going to let you know.

You’re in this proactive model where you intend to engage, not to dump but you got to be patient enough to let the audience respond and take care of itself, and then you’re going to have to back that up or respond on part as the author or organization.

You also have to have the mindset that you’re not the oracle and font of all wisdom. You are a part of a conversation and you’re talking to a lot of people who are, no doubt, a lot smarter than you are. You have to respect that, try to incorporate that, and think about ways. One of the things I did at the New York Times was introduce a case study feature where we would introduce a difficult business challenge that a business had gone through. They had either surmounted it or failed to solve the problem but it was in the past. We knew what the answer was but we wouldn’t give it away in the initial story.

“Here’s a challenge. What would you do if you faced this challenge?” We would solicit opinions. People would spend remarkable amounts of time offering advice and talking about what they would do. A week later, we would have the owner of that particular business come back and explain what they did and how it worked out. It created this learning experience that you could never do something like that in a newspaper or a print publication of any kind. I learned so much doing it. It was fun and great.

What’s interesting about what you’re saying is businesses struggle with social media and all these vehicles with how to respond to customers. Salespeople struggle with all the vehicles that a prospect can communicate with them. I’ve often said there are three levels of control. Reacting is probably the lowest level you could ever be. It’s your lowest odds.

Responding is probably you have some space in between a thought and an action. Being proactive is having a philosophy, strategy, or tactic that deals with a lot of the possibilities.

You learn and incorporate that so early in the way of the world. Leaders, especially small business leaders, struggle when you have a group of people coming in. I train a lot of Gen Z-ers and Millennials. Part of me says that it’s no different than our generation. The biggest difference is the fact that they’ve been the chief technology officer in their household from the time they were four years old so they think they have a seat at the table. There’s nothing wrong with that because we’ve said to all of our younger folks, “What’s the password to the internet?” They’ve always had a seat or some control.

A lot of organizations struggle with how to respond live because everything is so live. With everything that’s going on in the world, you get a retail outlet that all of a sudden has an opinion on something and they post it on the internet and they get a negative response one way or the other. Maybe you shouldn’t have put your politics out there.

I was taught a long time ago, “Don’t ask anybody how much they make. Don’t ask anybody about their religion. Don’t talk about politics. You’re probably in good shape.” I don’t know what we have forgotten at that but if you’re going to put it out there and then tether to what you believe, you are going to get opinions and you maybe should have thought of that proactively. You learn that way early with that engagement philosophy.

That’s true but that’s one example of many. You’re right on target with that. One of the things I learned doing this, and I’d love to know what you think, is I don’t think there’s any perfect training ground to be a business owner.

There’s no perfect training ground to be a business owner.

I don’t either.

MBA can help. I’m not going to say that doesn’t have any value. It does but there’s nothing like being in the owner’s seat and having to make those decisions. You’re talking about social media and what you share. That’s one particular but there are a million different examples like that.

Positive or negative. Some people can say, “My company went viral because I did.” I agree. People come to me and say, “I want to be an entrepreneur.” I ask them, “How did you arrive at that word? What’s precipitating this?” “I’m sick of working for the man or the woman.” “What does that mean?”

It means you’re a bad employee.

A lot of times, it could. The other thing is I had a guy come to me one time and he went to work for me. He was like, “I want to be an entrepreneur.” I said, “Let me ask you one scenario. Let’s say our revenues aren’t hitting this and we have payroll. Say we have $20,000 in the bank and the payroll is $35,000. How do you get there if you don’t have the money? Who gets paid first?” He kept including himself. I said, “Lesson one, you may not get paid.”

I had a partner one time where there was a minority stake in the business and a company wanted a refund. He goes, “I need it right away.” I go, “We’ll payroll next week and we’re not quite where we need to be.” This was years ago. He goes, “The customer always comes first.” I said, “That’s the biggest difference between you and me. I don’t believe the customer comes first. I believe the employee comes first. That’s probably why you sold me your business anyway.”

He goes, “We disagree. Unfortunately, for you, I’m okay with having a disagreement but this isn’t an equal partnership so thanks for your feedback. We’ll take care of the employees and then they’ll take care of the customer.” I’m not saying that’s right either. Some people say the customer comes first but like you’re saying, Loren, there’s no learning ground other than the learning ground you’re on.

What I’ve concluded, and tell me what you think because you would know better than me, is the closest thing you can come is to be part of a peer group and have other people around you on similar journeys that you can talk to. You can have the conversation that you had with your partner and open somebody’s eyes to the idea, “Wait a second, you haven’t thought about this. Maybe you shouldn’t pay yourself first. Maybe you should make sure those other people get paid and see what’s left.”

You nailed it, because philosophically speaking, there’s a difference between an abundance mentality and a scarcity mentality. If you’re going to be an entrepreneur, you probably need to have an abundance mentality. For being an entrepreneur, the ladder’s high but there’s no net. That comes down to risk at some level and how much risk. The last thing is Robert Kiyosaki said it the best. He had that frame like, “You’re either an employee or self-employed.” There’s a difference. Self-employed is when you have a job that you pay yourself for.

If you’re a business owner or an investor at some level, you’re going to migrate to all those things. You might need to make some leaps in all that thinking but you’re right. If you’re not talking to somebody, it’s a theory of AA too. Some people do well in AA because there’s a peer group and you’re talking to other people that you could empathize about your disease with. You can say, “I’m not alone.” That’s sometimes a good thing.

One of the principles of AA is you don’t give advice or tell people what to do. You say, “I’ve been in a similar situation and this is how I handled it and how it worked for me.” That’s exactly the most valuable thing and experience an entrepreneur can have. That’s why at 21 Hats, I have a monthly CEO forum that people can join. We have a couple of people around the world. We compare notes. Somebody has a question. Somebody has a challenge. I sometimes bring in guest speakers. That’s the idea on the podcast.

We do occasional in-person events where I don’t bring in speakers. I have a three-day peer group session. We start with dinner on Wednesday, go through lunch on Friday, and vote on the issues we want to discuss. In the one we did in May 2022, the issue that most people wanted to discuss was, “How big do you want your business to be?” We spent a lot of time. It got into a lot of issues like, “Do you want to take investors or not? Do you want to be your own boss? Do you want to bring somebody else to the table to control? Do you want to sell this? What’s its legacy?”

Let’s sum it up this way. Your career has been forming an empathy and an understanding or an EQ around this entrepreneurial person.

Yes. I like the puzzle-solving idea of, “Why do some businesses succeed and some fail?” Going back to when I covered fast-food in Columbus, one of the first things I learned about Wendy’s was that Dave Thomas started that chain with the idea that if you see a car pull into the parking lot, you immediately throw burgers on the grill and start cooking them. If they don’t order burgers, you throw the meat into the chili pot. The chili was part of the business model so that that meat wouldn’t go to waste. To me, that was solving a puzzle. That helped explain why the business succeeded. I always appreciated that part of it, plus what you said.

To bring this bird down for a landing, one of the things I always appreciated with you as you left some of those bigger publications was when I met you when you were on the Wharton Network on SiriusXM Radio. One of the things I admired when you were there and I still admire is that you are following that AA thing a little bit. You ask opinions for understanding as opposed to giving advice. You’re extremely good at guiding somebody to a conclusion. That’s your superpower. I’ve listened to you enough times. I’m racing to give advice all the time as a trainer.

That’s because you know stuff, Lance. All I know is how to ask questions.

No, but you know stuff too. If I cornered you, you give an opinion but I like how you get your audience to arrive at it, which is a superpower. It’s Socratic. It’s genius. I need to be doing more of that. I even appreciate how well you did that in a live conversation like this. You’ve been able to translate your career in writing to communicating it in several different ways through several vehicles, and then to pull expertise together to do that. That’s a superpower.

Here’s one big question for the audience. If you had to take an entrepreneur, a business, a leader, or a salesperson, moving forward from 2023 to 2033, what are the 3 to 5 skillsets or attitudes that you feel are going to set somebody apart moving forward? It can be things that they have in the past but I’m curious because you hear a lot of people.

Most people who start businesses start them because there’s something that they know well. It could be a skill like how to fix cars, frame pictures, make something, or cook food.

People don’t usually go into business because they do not know accounting or even sales necessarily. If you’re good at sales, correct me if I’m wrong because you’re the expert here, you probably become a salesperson and work at somebody else’s business at least initially.

If you start with starting a business, you’re doing it because you’re good at something. The interesting thing to me is you probably have to be pretty stubborn to do that because a lot of people are going to challenge you. Even some of your best friends. Maybe even your significant other is going to say, “Why do you want to do that? Go get a job. What are you thinking?”

It’s an expertise that you have.

If you’ve got this, you decide you want to start a business, you’re stubborn about it, and you’re not going to listen to all the naysayers. You’re going to do it. Here’s the thing. At some point, you have to stop being stubborn. You have to open your mind and listen to advice and other people’s experiences. That’s a difficult transition because entrepreneurs are headstrong. They know what they want to do. They have a vision. You can’t do it without that. You have to have that. At some point, you have to realize that you don’t know everything that other people have had relevant experience and you might have to listen to them. That’s a difficult transition. Having that open-minded mindset is crucial.

I also think that’s humbleness too because you usually get somebody confident and know exactly what they want. They have alpha traits but there has to be this humbleness. The hardest thing I had to do as an entrepreneur was to put a board together. I took a program by Clay Mathile who founded Aileron. I took a board class and they said, “Put a board together.” I remember my first couple of boards would go, “Stop selling.” I go, “I’m not selling.” They’re like, “Stop giving yourself advice. Do you want advice from us or do you want to give the advice?” That level of understanding or that humbleness to even ask for advice is important.

You were ahead of the game, Lance, because I know a lot of successful business owners who never constitute a board. Some of them want to be their own boss. They don’t want to be challenged. They want to do it their way. They know they’re going to make mistakes and they don’t want someone telling them that they’ve made a mistake.

I kept finding myself defending myself early on. I’m like, “This is why I did it.” They go, “Why do you need us? You got it.” I’m like, “You’re right.” It’s hard to do. That’s why getting that peer group like you talked about is so critical. Have expertise and humbleness. Seek understanding. You’re listening to understand, not to respond, it is probably if we’re going to bring it down to skillset. Give me one more.

The way things change so fast with all that we’ve been through, you have to be open-minded. It’s complicated. There’s somebody on my podcast who makes high-end conference tables. When the pandemic hit and everybody stayed home, there weren’t a lot of people looking to buy custom conference tables for $30,000, $40,000, $50,000, or more. It turned out his business held up for some interesting reasons. A lot of people told him, “You got to do what everybody else is doing. You have to pivot. People are working from home. You should be making a desk for home offices.”

He thought about that. He gave it serious thought and he decided, “Other people are doing that. They’re in mass production. I don’t do mass production. I can’t compete with IKEA or some other furniture manufacturer. They’re all way ahead of me. I got to stick with what I do and I’m going to stick with what I do.” It’s the company’s decision. It worked for him. It was the right decision for him. You have to know when to have an open mind and when to stick to your guns.

You have to know when to have an open mind and when to stick to your guns.

The open-mindedness comes through. It doesn’t mean you have to change. It means you have to consider the change. That’s genius. The one thing you don’t want to be, taking that gentleman for instance, is you don’t want to be the last of the buggy whip salespeople. If there are no more buggies or horses, stop selling the buggy whips.

You’re not going to believe this. I got a story for you real quickly. When I was a reporter with the Columbus Dispatch, I stumbled upon a guy in Columbus who was in his 80s and was still selling equipment for horses and buggies.

There is a large population in Ohio.

He had one customer. His customer was Anheuser-Busch.

No way. It’s so good. There’s a big Anheuser-Busch plant in Columbus, too. Here are the last two questions. If you had to advise a niece, nephew, or grandchild who’s 5 to 7 years old, maybe 8 years old max, and they said, “Uncle Loren, what does it mean to be successful,” you say what?

You find a way to do with your life what you want to do with it. You find a way to live and enjoy the things that you enjoy the way you want to enjoy them. You make yourself happy.

On your terms, you’ve been telling us about entrepreneurs. Here’s the last question. Besides my books, if you’re going to recommend a book and you could gift a book, what book do you gift the most?

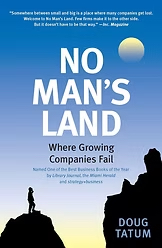

There’s one that’s not as well-known as many books which is one of the reasons I like to recommend it. It’s called No Man’s Land. It was written by Doug Tatum. He founded a fractional CFO business, which allowed him to see the inner workings of hundreds, if not thousands, of businesses. What he found is that every business that grows goes through a very difficult stage, which he called no man’s land where the things that worked initially stop working. It can be everything from employees to relationships with vendors and software tools across the board but the toughest ones are employees.

No Man’s Land: Where Growing Companies Fail

When you get into no man’s land, you end up having to have conversations where you say to someone who might be a relative or a close friend, “You helped me start this business. You’ve helped me build it. You’ve been incredibly loyal. You’ve worked hard but we’ve grown and reached a level where your experience is no longer sufficient. We need to bring in people who have a deeper understanding of whatever it is this person does. I’m going to have to figure out a way to make a change here.”

There’s no harder conversation than that. You can avoid it by not growing. If you grow pretty much at all, you can still stay relatively small and end up going through no man’s land but it’s inevitable if you grow. It’s difficult. He wrote a book that takes you through the best ways of dealing with those situations. I recommend that book highly.

I love it. I put it down on my list. Loren Feldman, I appreciate it. 21 Hats is great. I love everything you bring to the table. You made me rethink some things because I’m in a couple of those spots but the biggest thing with this conversation is from an entrepreneurial perspective, at least what I got is with your time at the New York Times and this ability to engage with the live community, it is what business is about. That can be proactive. It doesn’t have to be reactive. Having to do that means you have to listen and be aware and willing to make adjustments, change, or stand your ground. It’s well said. I love it. Thanks for your time.

Lance, this was an honor. Thank you so much for having me. I enjoyed it.

How do we get in contact with you?

You can go to 21Hats.com. That’s our website. You can subscribe to the daily email newsletter at 21Hats.Substack.com. You can find the podcast at 21 Hats Podcasts and wherever you get podcasts.

I’m going to be on soon. Yours truly, I can’t wait. Thanks. Loren, I appreciate your time.

Thank you, Lance.

Important Links

21 Hats Selling Is an Away Game No Man’s Land 21Hats.Substack.com 21 Hats Podcasts

About Loren Feldman

Loren Feldman is the founder and editor-in-chief of 21 Hats, an online community for business owners. He hosts the 21 Hats Podcast, which has been tracking the experiences of eight business owners in weekly conversations throughout the pandemic crisis, and he edits the 21 Hats Morning Report is a daily email newsletter for entrepreneurs. (More information here.) Previously, he was a senior editor covering entrepreneurship at Inc, Forbes, and the New York Times. He has also been editor-in-chief of Philadelphia magazine and executive editor of George magazine. He has spoken and moderated discussions on entrepreneurship at numerous conferences and seminars.